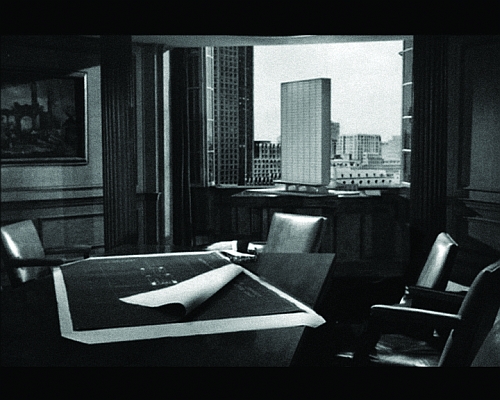

Société Réaliste’s full-length movie The Fountainhead, is based on the 1949 eponymous capitalist propaganda film written by Ayn Rand, the archpriestess of American libertarianism and author of some of its strongest cultural myths. The original studio movie (directed by King Vidor and featuring Gary Cooper and Patricia Neal in the main roles) tells the story of a Promethean modernist architect—a character based on the figure of Frank Lloyd Wright—fighting against the ambient collective decadence in the name of his personal genius. This original movie is a propagandist response to the Nazi and Soviet films of the prewar period. New York City, which is viewed as the idealized incarnation of capitalism, is at the centre of the script. A few years later Rand synthetized her zealous embracement of capitalist ideology in her “objectivist” theory, a deliberately globalizing and militant concept followed by numerous admirers such as Ronald Reagan and Alan Greenspan. In order to erase the plot of the original version, Société Réaliste removed the sound and every human presence from their version of The Fountainhead, thus reducing the film to its decor, i.e. its ideological architecture. It’s all about the atmosphere of the film, the fantasized portrait of the city of New York, the visual discourse about the architecture of a closed world: the glass tower of the titans of capitalism. Reminding us of what allowed our western world to become what it is and what it was been built on, the film points to the exterior signs which are still at work in the political economy of our technology-based era: comprised of powerful infrastructures, seductive environments and manipulative mediations. Are we only able to look beyond the smokescreens of what surround us?

Société Réaliste is an artists’ cooperative made up of Ferenc Gróf (1972) and Jean-Baptiste Naudy (1982) that was active for 10 years, from 2004 to 2014. Central to their activities is the exploration, subversion and deconstruction of the specific visual communication devices that have been developed and employed by institutions, governments and rulers, i.e., the representatives of power—in the fields of religion, politics, culture, art and finance—in order to position themselves. By exploring the representational and aesthetic roles of these agencies—including signs, logos, maps, symbols, typefaces, landmarks, emblems, statues or even buildings—in complex and much broader time and space contexts, the artists view them under a new light where they appear as a sort of “political cabinet of curiosities”, a critical, narrative implementation of design.